I want you to imagine something with me. Imagine that there was only one Holocaust museum in the whole United States. And imagine that only a handful of US Americans knew it existed. Now imagine that when anyone brought up the Holocaust or other examples of Jewish persecution, the average person gave responses such as “That was in the past. Why can’t you just let it go?” or “You’re only causing more divisiveness by bringing this up!”

As a Jewish person, this denial is unimaginable. It is also not what typically happens. Most of the time, if I bring up the Holocaust people are sympathetic and willing to discuss and condemn it.

The scenario of denial I painted above, however, is a very real experience for many African Americans.

Race is the topic that generates so much fear and discomfort that we either run away from it or lash out.

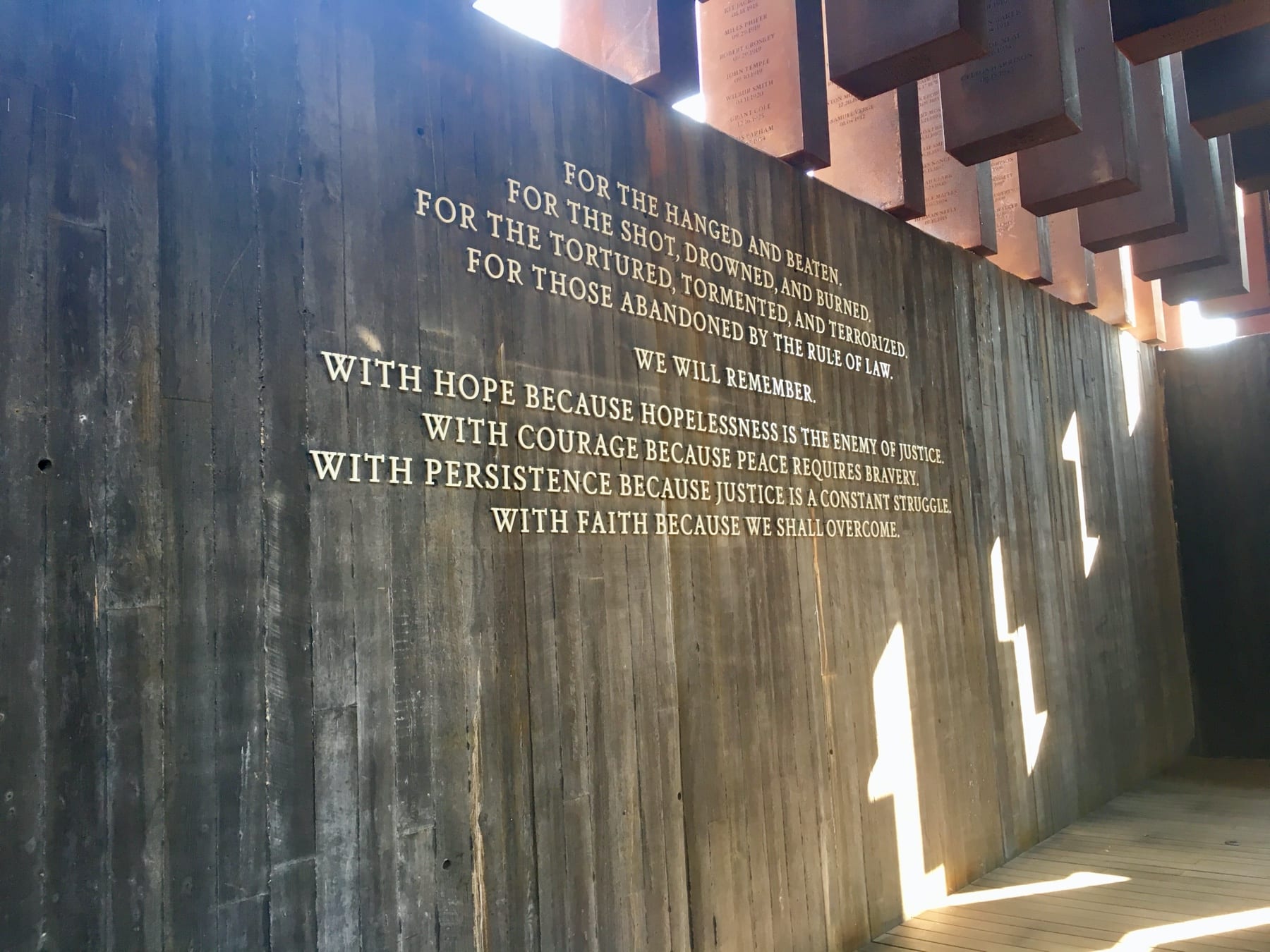

On a recent business trip to Montgomery, Alabama, I visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial to the thousands of victims of racial terror lynching between 1877 and 1950. This is the only such memorial in the nation, and most people I speak to had no idea it existed. I am saddened that I didn’t know it existed until recently.

Just for context, lynching is defined as follows: To put to death, especially by hanging, by mob action and without legal authority.

The memorial’s website says, “The lynching era left thousands dead; it significantly marginalized black people in the country’s political, economic, and social systems; and it fueled a massive migration of black refugees out of the South.”

In fact, the number of black refugees was about 6 million. Does that number sound familiar?

During my visit, I explored the memorial, a peaceful and haunting place with gardens, a waterfall, and 800 steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. I walked through the site with two African American colleagues, unable to imagine the experience they were having. One of them found her family’s county and took pictures to show her relatives. Was one of their names engraved on the monument?

As the debate rages on about the removal of Confederate statues (another subject for another time), I think a more important question is why aren’t there more monuments and museums dedicated to the victims and legacy of racial terror lynching? Critical history lessons do not come from statues. They come from careful research, primary sources, and documentation. This memorial has all of that and more.

As the debate rages on about the removal of Confederate statues (another subject for another time), I think a more important question is why aren’t there more monuments and museums dedicated to the victims and legacy of racial terror lynching? Critical history lessons do not come from statues. They come from careful research, primary sources, and documentation. This memorial has all of that and more.

I urge everyone to visit the memorial and the accompanying Legacy Museum.

https://museumandmemorial.eji.org/

For anyone thinking “this is all in the past – why do we have to keep talking about it?” I encourage you to read this report from the non-profit EJI, which documents painstaking research on the ongoing legacy of enslavement and lynching: https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/

What we do not own owns us. I know it is painful, and the topic of race seems to generate fear and discomfort like nothing else, especially among whites. But the time is now. If we own our history and its legacy, healing can begin.

If your organization would like to talk about how to prevent biases from operating in the workplace, contact us at [email protected] or 770-936-9209.