Imagine a university with a solid reputation. People come from all over the region to attend, to improve their minds, and to provide themselves with new opportunities. The students discover their academic strengths and study everything from business to physics.

The classrooms at this university look fairly standard for a U.S.-based institution. Students come in to classrooms, take their seats, listen to professors, and take notes. They study at night and if they work hard, they earn their degree.

One day, two students who looked different from anyone who had attended the school before decided to enroll. Like most of the other students of the university, they had been top performers in high school and wanted to continue their education. They had all of the necessary requirements for entrance, so they went to the registration office. But as they walked to the door, they noticed a crowd. The people told the students to go back from where they came, that they had no business being there. The students noticed agitation among the crowd; the leader of the crowd blocked the door and would not admit the students until ordered to by the authorities.

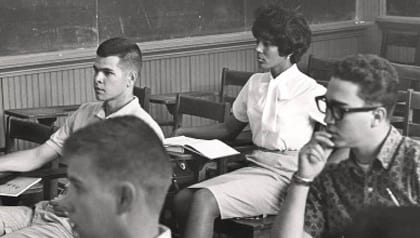

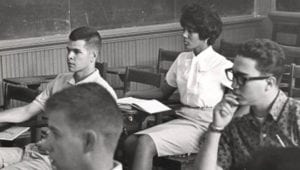

Does this sound familiar? You may recognize and draw a parallel to the story often referred to as Stand in the Schoolhouse Door, the attempt by two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood to enroll in the University of Alabama, Mobile in 1963. This incident came nine years after segregation of public schools was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Malone and Hood met all of the requirements needed to enter the university, but when they arrived to register and pay their fees, they were blocked at the door by then-Governor George Wallace. Federal authorities tried to allow the students to enter but Wallace remained firm, giving a speech until the National Guard was called to remove him. He stepped aside at that point.

This video from the University of Alabama marks the 40th anniversary of the incident and features an interview with Vivian Malone.

Why do I recount this story for you now? Because it demonstrates the importance of a skill that we need to master in today’s challenging global climate: Learning to distinguish between the thing and our thoughts about the thing.

What does that mean? Let’s look at the University of Alabama incident. What was the thing? If we looked at only what could be verified with the senses, we would have seen two African Americans walking to the entrance of Foster Auditorium. That is all. Everything that Governor Wallace and the other protestors acted upon was the result of their thoughts about the thing, their fear of their way of life being threatened (Wallace particularly emphasized states rights) and their struggle with change. Wallace had wanted to preserve segregation, stating “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

While we can empathize with that struggle (every human being has feared change at some point), we must recognize the difference between what actually happened and what was feared to happen.

After Hood and Malone attended the University of Alabama, both earned their degrees, with Hood leaving two months after enrolling and returning later to earn a doctorate. Governor Wallace, who had changed his views significantly over the years, was set to give Hood his degree in 1997, but poor health prevented this. In 1996, Wallace gave the Lurleen B. Wallace Award for Courage to Malone. He told her that he regretted his actions 33 years ago. Both Malone and Hood forgave Wallace.

The thoughts about the thing, not the thing, caused the struggle.

I invite you to consider this concept in today’s climate and in your personal interactions. Thoughts will come. They may even be thoughts you don’t want about a particular culture or person. Let them be, but recognize them for what they are. Will you act on what’s in front of you and what’s verifiable, or on what you fear will arise from that situation? This doesn’t mean that you never take action against a threat. It means that you have the skill to distinguish between the two, and that you make decisions accordingly.

This skill, in my opinion, can save lives. It can prevent us from repeating history and allow for a more thoughtful response to the challenges we face today.